Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the growing antisemitism on America’s campuses is just how long those in the best position to do something about it — alumni, major donors, the legislative overseers of state schools, students’ parents, and less radical professors — continued to overlook its motivating ideology. Academic sympathy for doing whatever it takes to eliminate those groups the left deems responsible for unequal access to society’s goods and services goes all the way to the mid-1960s, when neo-Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse published his influential essay “Repressive Tolerance.”

In the decades since, notes Manhattan Institute Senior Fellow James Piereson, “The old-time curriculum through which young Americans learned about the virtues of free institutions and progress through science and free inquiry has given way to a new approach that asserts these ideals are but smoke screens allowing white Europeans and Americans to govern the planet, while oppressing minority groups and despoiling the environment.”

Colleges and universities have not only attacked Western civilization and its aspirational values but have permitted the increasingly aggressive suppression of any event or person not echoing the newer, darker worldview. What long ago started as mostly peaceful protesting against prominent conservatives speaking on campus has since morphed into today’s vicious “cancel culture” and, as the public is now learning, frequent antisemitic incidents at Yale, Columbia, the University of Pennsylvania, Stanford, and elsewhere.

To their credit, many of the wealthy donors who are finally closing their wallets to the colleges or universities they once generously supported are not trying to hide their longtime awareness of an ever more venomous progressivism. Their statements so far have been not along the lines of, “I’m shocked by this unexpected outburst of Jew hatred,” but rather, as Renaissance Technologies venture capitalist David Magerman recently put it, “I was just pushed over the edge by the equivocation of the (University of Pennsylvania’s) response.”

In effect, Magerman and his fellow mega-donors are saying that, while they had for some time sensed something amiss with the institutions they were funding, they continued clinging to a hopeful outlook. “These are just college kids,” the funders likely told themselves, “and they’ll get over this radicalism when they get older.” Or maybe they thought “there aren’t as many progressive professors and administrators as it seems — they’re just noisier than the others.” Perhaps the billionaires even thought that “the example of my giving will change the way some faculty and students think about successful people.”

The good news is that serious efforts to counter progressivism, not only at colleges and universities, but at charities, museums, government agencies, and other effected institutions are finally under way. For example, House Ways and Means Committee chairman Rep. Jason Smith (R, Missouri) is looking into whether any nonprofit organization which promotes a hateful ideology can legitimately claim tax-exempt status. And in addition to halting his personal giving to the University of Pennsylvania, Apollo Global Management CEO Marc Rowan is leading an all-out campaign to fire the school’s president, Elizabeth Magill, as well as the chairman of its board of trustees, Scott Bok.

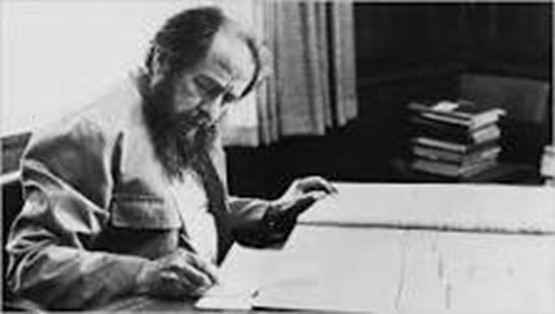

Yet history suggests that any lasting remedy for the kind of repressive ideology which has taken over higher education, and through it much of the rest of civil society, must go beyond monetary and policy solutions. As the dissident Russian writer Alexsandr Solzhenitsyn famously observed, it is not possible for any intellectual tyranny to thrive unless the thinking of its adherents has somehow been encouraged by those outside the circle of true believers.

If concerned citizens really want to combat a corrupt belief system, he wrote in his essay “The Smatterers,” the place to start is with their own tendency during everyday conversation to let pass those statements which imply some kind of sympathy for it. Such indulgence mostly occurs for the seemingly innocent reason of wanting to avoid an awkward moment or subsequent argument, but the unintended effect is to suggest the listener’s approval for the opinion just expressed. As when a parent overlooks the fact that his child’s excitement over a new college sociology course is peppered with oddly judgmental or impractical ideas.

All this does not mean one has to “go around preaching the truth at the top of your voice,” Solzhenitsyn was quick to stipulate. It “doesn’t even mean muttering what you really think in an undertone.” (Indeed, for his readers in the old Soviet Union, these would have been very risky responses.) It simply means, as Solzhenitsyn put it, “Never say what you don’t think or let someone assume it.”

And while such an attitude might seem too casual or insignificant to have much of an effect, every misguided social philosophy has internal contradictions which are aggravated when they meet a certain kind of resistance. Not a sermon or heated argument, but the quiet refusal to “carelessly assent” to that which violates one’s sense of what is real and right.

The power of this conversational non-cooperation lies not in its intensity but its timing. It must be “on the spot,” in Solzhenitsyn’s words, where it can be felt by the speaker, not merely fantasized in the back of the listener’s mind until the subject under discussion has conveniently changed. Wrongheaded statements must be allowed to create an awkward pause “without worrying whether others will follow in our footsteps and without looking around to see if the rest of the population is catching the habit.”

Interestingly, no group would appear to agree more with this analysis than those progressive leaders who for decades have been obsessed with the politically correct suppression of nuanced behavior (so-called “microaggressions”) throughout society. Trigger warnings, safe spaces, calculations of “privilege” — what are these social inventions really about, if not to shield a weak ideology from the kind of critical reexamination that too many bemused smiles, blank stares, and cocked eyebrows will inevitably prompt?

If there is anything to be learned from the experience of Alexsandr Solzhenitsyn and all the other Soviet dissidents who helped bring down Russia’s communist empire it is that preserving a free society is not just the job of wealthy philanthropists, influential editorialists, and powerful politicians. There is a critical role for everyone with a willingness to prioritize something more important than frictionless conversation.